I read Chris Anderson’s Wired column (that in many ways initiated the current discussion of The Long Tail) over Thanksgiving weekend 2004. I remember distinctly being at my uncle’s house in rural British Columbia sitting on an old couch in his eclectic second floor (see the photos- BTW I love this house, so much visual stimulation that it provides a great place for new ideas to flower)

and reading the article. At the time it seemed interesting but didn’t really hit home. I wasn’t quite able to see how this concept of the long tail applied to my life but I was intrigued. In retrospect, I realize that I was hanging out with a person (my uncle) that has lived most of his life pretty far out on the tail of traditional culture.

Again I've highlighted my comments in blue throughout the text below. The italics in the text are transcribed from the book. The bold is my editorial emphasis.

There are three primary concepts from this book that I wanted to mention. The first one has to do with time and the effect that our filters are having on the traditional time effect.

Page 142

“But there is another factor that influences popularity: age. Just as things of broad appeal tend to sell better than things of narrow appeal, new things tend to sell better than old things.”

“If you think about it, today’s hit is tomorrow’s niche. Almost all products, even hits, see their sales decay over time. Twister was the number two movie of 1996, but it’s DVD version is now outsold two-to-one on Amazon by a 2005 History Channel documentary on the French Revolution.

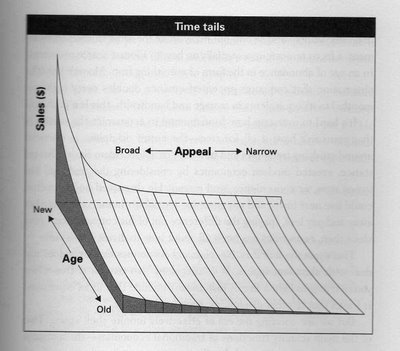

“Einstein described time as the fourth dimension of space; you can think of it equally as the fourth dimension of the Long Tail. Both hits and niches see their sales slow over time; hits may start higher, but they all end up down the Tail eventually. The research to quantify this conclusion is continuing, but conceptually the picture looks like the graph on the next page [see image titled "Time tails"].

“What’s particularly interesting about time and the Long Tail is that Google appears to be changing the rules of the game. For online media, like media anywhere, there is a tyranny of the new. Yesterday’s news is fish wrap, and once content falls off the front page of a Web site, its popularity plummets. But as sites find more and more of their traffic coming from Google, they’re seeing this rule break.

“Google is not quite time-agnostic, but it does measure relevance mostly in terms of incoming links, not newness. So when you search for a term, you’re more likely to get the best page than the newest one. And because older pages have more time to attract incoming links, they sometimes have an advantage over the newer ones. The result is that the usual decay of popularity for blog posts and online news pages is now much more gradual than it was thanks to the amount of traffic that comes via search. Google is in a sense serving as a time machine, and we’re just now being able to measure the effect that has on publishing, advertising, and attention.”

I think the impact filters such as Google are having in regard to finding things that are “older” and therefore in the tail is incredible. Anderson provides several other examples of media that was overlooked when it was produced that resurfaced later due to the technologies available in the filters. He begins chapter 1 with the story of Touching the Void and how this story resurfaced years after it was first written thanks to Amazon’s “people who bought also bought…” feature.

The second idea I wanted to mention has to do with microculultures. Thanks to the filter technologies we are finally able to indulge many of our long tail preferences and interests. I think this is great but it can sure make it difficult to talk to my neighbors. We just don’t share the same reference points the way we used to.

Page 182

"I decided to test other cultural touchstones to see if they were as widely held as I had thought. I started by running a few other clichés from my little online world past real-world friends: “All Your Base Are Belong To Us”; “More Cowbell!” “I for one welcome our new [fill in the blank] overlords,” and so on. Turns out that these snippets of culture that I thought were ubiquitous are actually pretty obscure, even in my own office. When I took an informal poll at a public relations conference at which I was speaking, I found that only about 10 percent of the audience had heard of any of them – and for each phrase it was a different 10 percent.

"What does this show? It shows that my tribe is not always your tribe, even if we work together, play together, and otherwise live in the same world. Same bed, different dreams.

"The same Long Tail forces and technologies that are leading to an explosion of variety and abundant choice in the content we consume are also tending to lead us into tribal eddies. When mass culture breaks apart, it doesn’t re-form into a different mass. Instead, it turns into millions of microcultures, which coexist and interact in a baffling array of ways.

"As a result, we cannot treat culture not a one big blanket, but as the superposition of many interwoven threads, each of which is individually addressable and connects different groups of people simultaneously.

In short, we’re seeing a shift from mass culture to massively parallel culture. Whether we thing "of it this way or not, each of us belongs to many different tribes simultaneously, often overlapping (geek culture and LEGO), often not (tennis and punk-funk). We share some interests with our colleagues and some with our families, but not all of our interests. Increasingly, we have other people to share them with, people we have never met or even think of as individuals (e.g., blog authors or playlist creators).

"Virginia Postrel observed that the variety boom is nothing more than a reflection of the diversity inherent in any population distribution:

- Every aspect of human identity, from size, shape, and color to sexual proclivities and intellectual gifts, comes in a wide range. Most of us cluster somewhere in the middle of most statistical distributions. But there are lots of bell curves, and pretty much everyone is on a tail of t least one of them. We may collect strange memorabilia or read esoteric books, hold unusual religious beliefs or wear odd-sized shoes, suffer rare diseases or enjoy obscure movies.

I think we’re just at the beginning of discovering how this trend is going to impact our communities. Part of the reason I write this blog is to give other people a window into the microcultures that I’m spending my time in.

The third idea I wanted to touch on has to do with “who is in control of all of this”. The following passage discusses this in the world of newspapers and bloggers but I think that this passage could easily apply to music, film/video and other types of content just as easily.

Page 188

"In Letters to a Young Contrarian, Christopher Hitchens writes that he wakes up every morning and checks his vital signs by grapping the front page of the New York Times: “’All the News That’s Fit to Print,’ it says. It’s been saying that for decades, day in and day out. I imagine that most readers of the canonical sheet have long ceased to notice the bannered and flaunted symbol of its mental furniture. I myself check every day to make sure that it still irritates me. If I can still exclaim, under my breath, why do they insult me and what do they take me for and what the hell is it supposed to mean unless it’s an obviously complacent and conceited and censorious as it seems to be, then at least I know that I still have a pulse.”

"As Jerry Sienfeld quips, “It’s amazing that the amount of news that happens in the world every day always just exactly fits the newspaper.”

"The reality, slogan aside, is that the New York Times now competes not only with other New York City newspapers and newspapers elsewhere, but also with the collective wisdom and information of everyone online. Authority is in the eye of the beholder; it is not innate to the institution itself. It is a credit to the Times journalists and editors that they do so well, continuing to break news and set the agenda, despite this. But news and information is clearly no longer the exclusive domain of professionals.

"With an estimated 15 million bloggers out there, the odds that a few will have something important and insightful to say are good and getting better. And as our filters improve, the odds that we’ll see them are getting better, too. From a mainstream media perspective, this is simply more competition, whatever the source. And some audiences will prefer it. Like it or not, fragmentation is inevitable."

Now that I think about this a bit more I realize that I’ve been using bloggers as a tool to point me to specific media items. I often like the filters that bloggers provide better than skimming the list of headlines on a newspaper home page.

No comments:

Post a Comment